The Medes were an people of Indo-Iranian (Aryan) origin who inhabited the western and north-western portion of present-day Iran. By the 6th century BC (prior to the Persian invasion) the Medes were able to establish an empire that stretched from Aran (the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan) to Central Asia and Afghanistan. Today’s population of the western part of the Iranian Plateau (including many Persian-speakers, Kurds and Azeris) consider themselves to be descended from the ancient Medes.

The Medes were an people of Indo-Iranian (Aryan) origin who inhabited the western and north-western portion of present-day Iran. By the 6th century BC (prior to the Persian invasion) the Medes were able to establish an empire that stretched from Aran (the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan) to Central Asia and Afghanistan. Today’s population of the western part of the Iranian Plateau (including many Persian-speakers, Kurds and Azeris) consider themselves to be descended from the ancient Medes.

Apart from a few personal names, the language of the Medes is almost entirely unknown. It was most likely similar to the Avestan and Scythian languages.

Herodotus lists the names of six Mede tribes or castes. Some of these are similar to tribal names of the Scythians, suggesting a definitive link between these two groups.

- The Busae group is thought to derive from the Persian term buza meaning indigenous (i.e. not Iranian). Whether this was based on an originally Iranian term, or their own name, is unknown.

- The second group is called the Paraetaceni, or Parae-tak-(eni) in Persian, and denotes nomadic inhabitants of the mountains of Paraetacene. This name recalls the Scythian Para-la-ti, the people of Kolaxis, believed to represent the common people in general, but whom Herodotus calls the “Royal Scythians”.

- The third group is called Strukhat.

- The fourth group is the Arizanti, whose name is derived from the words Arya (noble), and Zantu (tribe, clan).

- The fifth group were the Budii, found also among the Black Sea Scythians as Budi-ni. Buddha was of the tribe Budha, the Saka (eastern Scythian) form of the name.

- The sixth tribe were the Magi…They were a hereditary caste of priests of the Zurvanism religion that evolved out of Zoroastrianism. The name Magi implies a link with the Sumerians, who called their language Emegir, over time becoming simplified to Magi. Hungarian tradition also traces pre-European Magyar (Hungarian) ancestry back to the Magi. In time, the Sumerian-influenced religion of the Magi was suppressed in favour of a more purely Iranian form of Zoroastrianism, itself evolved from its somewhat dualist beginnings into the monotheistic faith that it is today (also known as Parsi-ism).

The origin and history of the Medes is quite obscure, as we possess almost no contemporary information, and not a single monument or inscription from Media itself. The story that Ctesias gave (a list of nine kings, beginning with Arbaces, who is said to have destroyed Nineveh about 880 BC, preserved in Diod. ii. 32 sqq. and copied by many later authors) has no historical value whatever; though some of his names may be derived from local traditions.Josephus relates the Medes (OT Heb. Madai) to the biblical character, Madai, son of Japheth. “Now as to Javan and Madai, the sons of Japhet; from Madai came the Madeans, who are called Medes, by the Greeks” Antiquities of the Jews, I:6.

Other ancient historians including Strabo, Ptolemy, Herodotus, Polybius, and Pliny, mention names such as Mantiane, Martiane, Matiane, Matiene, to designate the northern part of Media.

We can see how the Iranian element gradually became dominant; princes with Iranian names occasionally occur as rulers of other tribes. But the Gelae, Tapuri, Cadusii, Amardi, Utii and other tribes in northern Media and on the shores of the Caspian may not have been Iranian stock. Polybius (V. 44, 9), Strabo (xi. 507, 508, 514), and Pliny (vi. 46), considered the Anariaci to be among these tribes; but their name, meaning the “not-Arians”, is probably a comprehensive designation for a number of smaller indigenous tribes.

The Medes, people of the Mada, (the Greek form “Μηδοί” is Ionian for Madoi), appear in history first in 836 BC. Earliest records show that Assyrian conqueror Shalmaneser II received tribute from the “Amadai” in connection with wars against the tribes of the Zagros. His successors undertook many expeditions against the Medes (Madai).

At this early stage, the Medes were usually mentioned together with another steppe tribe, the Scythians, who seem to have been the dominant group. They were divided into many districts and towns, under petty local chieftains; from the names in the Assyrian inscriptions, it appears they had already adopted the religion of Zoroaster.

An Assyrian military report from 800 BC lists 28 names of Mede chiefs, but only one of these is positively identified as Iranian. A second report from c. 700 BC lists 26 names; of these, 5 seem to be Iranian, the others are not.

Sargon in 715 BC and 713 BC subjected them up to “the far mountain Bikni,” i.e. the Elbruz (Damavand) and the borders of the desert. If the account of Herodotus may be trusted, the Medes’ dynasty derived its origin from Deioces (Daiukku), a Mede chieftain in the Zagros, who was, along with his kinsmen, transported by Sargon to Hamath (Haniah) in Syria in 715 BC. This Daiukku seems to have originally been a governor of Mannae subject to Sargon, prior to his exile.

In spite of repeated rebellions by the early chieftains against the Assyrian yoke, the Medes paid tribute to Assyria under Sargon’s successors, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Assur-bani-pal, whenever these kings marched in with their fierce armies. Assyrian forts located in Median territory (Zagros Mtns) at the time of Esarhaddon’s campaign (ca. 676) included Bit-Parnakki, Bit-kari and Harhar (Kar-Sharrukin).

In the second half of the 7th century BC, the Medes gained their independence and were united by a dynasty. The kings who established the Mede Empire are generally recognized to be Phraortes and his son Cyaxares. They were probably chieftains of a nomadic Mede tribe in the desert and on the south shore of the Caspian, the Manda, mentioned by Sargon, and they likely founded the capital at Ecbatana. The later Babylonian king Nabonidus also designated the Medes and their kings always as Manda. According to Herodotus, the conquests of Cyaxares the Mede were preceded by a Scythian invasion and domination lasting twenty-eight years (under Madius the Scythian, 653-625 BC). The Mede tribes seem to have come into immediate conflict with a settled state to the West known as Mannae, allied with Assyria. Assyrian inscriptions state that the early Mede rulers, who had attempted rebellions against the Assyrians in the time of Esarhaddon and Assur-bani-pal, were allied with chieftains of the Ashguza (Scythians) and other tribes – who had come from the northern shore of the Black Sea and invaded Armenia and Asia Minor; and Jeremiah and Zephaniah in the Old Testament also agree with Herodotus that a massive invasion of Syria and Palestine by northern barbarians took place in 626 BC. The state of Mannae was finally conquered and assimilated by the Medes in the year 616 BC.In 612, Cyaxares conquered Urartu, and with the help of Nabopolassar the Chaldean, succeeded in destroying the Assyrian capital, Nineveh; by 606, the remaining vestiges of Assyrian control. From then on, the Mede king ruled over much of Iran, Assyria and northern Mesopotamia, Armenia and Cappadocia. His power was very dangerous to his neighbors, and the exiled Jews expected the destruction of Babylonia by the Medes (Isaiah 13, 14m 21; Jerem. 1, 51.).

When Cyaxares attacked Lydia, the kings of Cilicia and Babylon intervened and negotiated a peace in 585 BC, whereby the Halys was established as the Medes’ frontier with Lydia. Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon married a daughter of Cyaxares, and an equilibrium of the great powers was maintained until the rise of the Persians under Cyrus.

About the internal organization of the Mede Empire, we know that the Greeks adopted many ceremonial elements of the Persian court, the costume of the king, etc., through Media.

In 553 BC Cyrus, king of Persia, rebelled against his suzerain, the Mede King Astyages, son of Cyaxares; he finally won a decisive victory in 550 BC resulting in Astyages’ capture by his own dissatisfied nobles, who promptly turned him over to the triumphant Cyrus. Thus were the Medes subjected to their close kin, the Persians. In the new empire they retained a prominent position; in honor and war, they stood next to the Persians; their court ceremony was adopted by the new sovereigns, who in the summer months resided in Ecbatana; and many noble Medes were employed as officials, satraps and generals. After the assassination of the usurper Smerdis, a Mede Fravartish (Phraortes), claiming to be a scion of Cyaxares, tried to restore the Mede kingdom, but was defeated by the Persian generals and executed in Ecbatana (Darius in the Behistun inscr.). Another rebellion, in 409, against Darius II (Xenophon, Hellen. ~. 2, 19) was of short duration. But the non-Aryan tribes to the north, especially the Cadusii, were always troublesome; many abortive expeditions of the later kings against them are mentioned. Under Persian rule, the country was divided into two satrapies: the south, with Ecbatana and Rhagae (Rai), Media proper, or Greater Media, as it is often called, formed in Darius’ organization the eleventh satrapy (Herodotus iii. 92), together with the Paricanians and Orthocorybantians; the north, the district of Matiane (see above), together with the mountainous districts of the Zagros and Assyria proper (east of the Tigris) was united with the Alarodians and Saspirians in eastern Armenia, and formed the eighteenth satrapy (Herod. iii. 94; cf. v. 49, 52, VII. 72).When the Persian empire decayed and the Cadusii and other mountainous tribes made themselves independent, eastern Armenia became a special satrapy, while Assyria seems to have been united with Media; therefore Xenophon in the Anabasis always designates Assyria by the name of “Media.”

Alexander occupied Media in the summer of 330 BC. In 328 he appointed as satrap a former general of Darius called Atropates (Atrupat), whose daughter was married to Perdiccas in 324, according to Arrian. In the partition of his empire, southern Media was given to the Macedonian Peithon; but the north, far off and of little importance to the generals squabbling over Alexander’s inheritance, was left to Atropates. While southern Media, with Ecbatana, passed to the rule of Antigonus, and afterwards (about 310) to Seleucus I, Atropates maintained himself in his own satrapy and succeeded in founding an independent kingdom. Thus the partition of the country, that Persia had introduced, became lasting; the north was named Atropatene (in Pliny, Atrapatene; in Ptolemy, Tropatene), after the founder of the dynasty, a name still said to be preserved in the modern Azerbaijan.The capital of Atropatene was Gazaca in the central plain, and the castle Phraaspa, discovered on the Araz river by archaeologists in April 2005. The kings had a strong and warlike army, especially cavalry (Polyb. v. 55; Strabo xi. 253). Nevertheless, King Artabazanes was forced by Antiochus the Great in 220 BC to conclude a disadvantageous treaty (Polyb. v. 55), and in later times, the rulers became dependent in turn upon the Parthians, upon Tigranes of Armenia, and in the time of Pompey who defeated their king Darius (Appian, Mithr. 108), upon Antonius (who invaded Atropatene) and upon Augustus of Rome. In the time of Strabo (AD 17), the dynasty still existed; later, the country seems to have become a Parthian province.

Atropatene is that country of western Asia which was least of all other countries influenced by Hellenism; there exists not even a single coin of its rulers. But the opinion of modern authors that it had been a special refuge of Zoroastrianism, is partly based on a folk etymology of the name (explained as “country of fire-worship”), partly on Zoroastrian traditions, including traditions regarding the birthplace of Zoroaster, and partly because of the natural phenomenon of flames escaping from rock fissures, occurring throughout the former territory of Atropatene. There can be no doubt that the kings adhered to the Persian religion; though it may not have been deeply rooted among their subjects, especially among the non-Aryan tribes.

Southern Media remained a province of the Seleucid Empire for a century and a half, and Hellenism was introduced everywhere. Media was surrounded everywhere by Greek towns, in pursuance of Alexander’s plan to protect it from neighboring barbarians, according to Polybius (x. 27). Only Ecbatana retained its old character. But Rhagae became the Greek town Europus; and with it Strabo (xi. 524) names Laodicea, Apamea Heraclea or Achais. Most of them were founded by Seleucus I and his son Antiochus I.

In 221, the satrap Molon tried to make himself independent (there exist bronze coins with his name and the royal title), together with his brother Alexander, satrap of Persis, but they were defeated and killed by Antiochus the Great. In the same way, the Mede satrap Timarchus took the diadem and conquered Babylonia; on his coins he calls himself the great king Timarchus; but again the legitimate king, Demetrius I, succeeded in subduing the rebellion, and Timarchus was slain. But with Demetrius I, the dissolution of the Seleucid Empire began, brought about chiefly by the intrigues of the Romans, and shortly afterwards, in about 150, the Parthian king Mithradates I conquered Media (Justin xli. 6).

From this time Media remained subject to the Arsacids or Parthians, who changed the name of Rhagae, or Europus, into Arsacia (Strabo xi. 524), and divided the country into five small provinces (Isidorus Charac.). From the Parthians, it passed in AD 226 to the Sassanids, together with Atropatene.

By this time the older tribes of Aryan Iran had lost their distinct character and had been amalgamated into one people, the Iranians. The revival of Zoroastrianism, enforced everywhere by the Sassanids, completed this development. It was then that Atropatene became a principal seat of fire-worship, with many fire-altars. Arsacia (Rhagae) now became the most sacred city of the empire and the seat of the head of the Zoroastrian hierarchy; the Sassanid Avesta and the tradition of the Parsees therefore consider Rhagae as the home of the family of the Prophet Zoroaster.

A Magus (plural Magi, from Latin, via Greek μάγος from Old Persian maguš) was a Zoroastrian astrologer-priest from ancient Persia, from which is derived the terms magic, magician, and also referred to as a sorcerer or wizard. The English term may also refer to a shaman.The best known Magi are the Wise Men from the East in the Bible.

The Greek word is attested from the 5th century BC as a direct loan from Old Persian maguš. The Persian word is a u-stem adjective from an Indo-Iranian root *magh “powerful, rich” also continued in Sanskrit magha “gift, wealth”, magha-vant “generous” (a name of Indra). Avestan has maga, magauuan, probably with the meanings “sacrifice” and “sacrificer”.

The Indo-European root appears to have expressed power or ability, continued e.g. in Greek mekhos (see mechanics) and in Germanic magan (English may), magts (English might, the expression “might and magic” thus being a figura etymologica). The original significance of the name for the Median priests thus seems to have been “the powerful”. Modern Persian Mobed is derived from an Old Persian compound magu-pati “lord priest”.

The plural Magi entered the English language in ca. 1200, referring to the Magi mentioned in Matthew 2:1, the singular being attested only considerably later, in the late 14th century, when it was loaned from Old French in the meaning magician together with magic.

In Persian, Magi is meguceen, meaning “Fire Worshipper.” Its the origin of the word magician.

The term mag, may also come from the Hebrew magdal, meaning “tower.” The Magi would then be the “men of the tower” or “towers.” The towers refer to the pyramids of Egypt. In the Nativity story, the Magi were said to have come from Egypt.

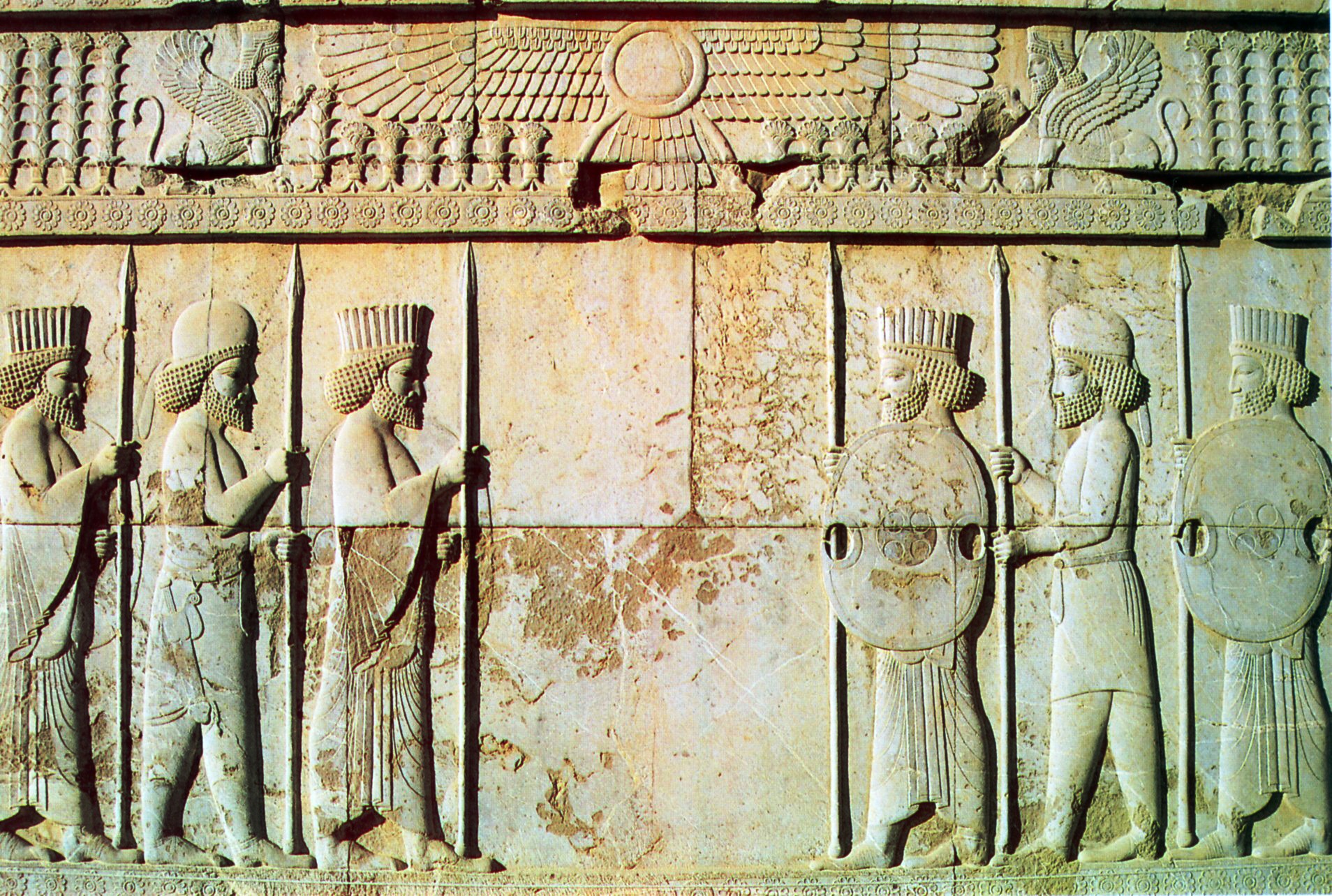

According to Herodotus, the Magi were the sacred caste of the Medes. They organized Persian society after the fall of Assyria and Babylon. Their power was curtailed by Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire, and by his son Cambyses II; the Magi revolted against Cambyses and set up a rival claimant to the throne, one of their own, who took the name of Smerdis. Smerdis and his forces were defeated by the Persians under Darius I. The sect of the Magi continued in Persia, though its influence was limited after this political setback.During the Classical era (555 BCE – 300 CE), some Magi migrated westward, settling in Greece, and then Italy. For more than a century, Mithraism, a religion derived from Persia, was the largest single religion in Rome. The Magi were likely involved in its practice.

The Book of Jeremiah (39:3, 39:13) gives a title rab mag “chief magus” to the head of the Magi, Nergal Sharezar (Septuagint, Vulgate and KJV mistranslate Rabmag as a separate character).

After invading Arabs succeeded in taking Ctesiphon in 637, Islam replaced Zoroastrianism, and the power of the Magi faded.

While in Herodotus, magos refers to either a member of the tribe of the Medes (1.101), or to one of the Persian priests who could interpret dreams (7.37), it could also be used for any enchanter or wizard, and especially to charlatans or quacks (see also goetia), especially by philosophers such as Heraclitus who took a skeptical view of the art of an enchanter, and in comic literature (Lucian’s Lucios or the Ass). The use of magoi in Matthew 2:1 of course is that of Hdt 7.37.In Hellenism, magos started to be used as an adjective, meaning “magical”, as in magas techne “ars magica” (e.g. used by Philostratus).

Mage, rather than magus, is the spelling usually encountered for magic-user characters in role-playing games and fantasy fiction. An exception is the game Ars Magica, where the main characters are known as magi.Many references to the three magi can be found in various games and shows. For example, in the Neon Genesis Evangelion anime/manga series, a supercomputer (called “MAGI”) is divided in three distinct parts, all of which are named after the Magi.

In the video game Chrono Trigger, the three Gurus, of Life, Time, and Reason, are also named after the Magi and, through the course of the game, give key items to the player. Furthermore, one of the game’s main characters is named Magus, and another Cyrus.